Latest Features

More Stories

Dread is releasing a siege movie with an interesting spin next week, as you can see below from the Last…

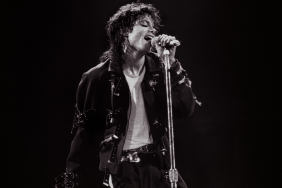

The Michael release date for Lionsgate’s highly anticipated Michael Jackson biopic from Antoine Fuqua has been revealed. The upcoming Jaafar…

The Exorcist: Deceiver release date has been delayed as it has been taken off Universal Pictures’ upcoming release calendar. The…

Netflix has dropped the official Players trailer for its latest romantic comedy movie starring Gina Rodriguez and Tom Ellis. The…

AMC Networks has unveiled the trailer for the Giancarlo Esposito-led crime thriller Parish. Set to hit AMC and AMC+ this…

ComingSoon is debuting an exclusive The Bleacher poster for the surreal animated short film, which is set to premiere at…

Warner Bros. is hoping to move forward with a sequel to 2014’s Edge of Tomorrow starring Tom Cruise and Emily…

Fallout 4’s highly anticipated Fallout London mod finally has a release date. The upcoming total conversion mod will take players…

Another One Piece Pirate Warriors 4 DLC trailer has been unveiled, showing off three characters from One Piece Film: Red.…

Quiver Distribution has released the official Lights Out trailer for its upcoming R-rated action thriller. It stars Frank Grillo as…

Ex Machina and Tomb Raider actress Alicia Vikander will be starring alongside Cate Blanchett in Guy Maddin’s new project, Rumours,…

Guy Ritchie‘s next movie already has quite the duo set to lead it, as the upcoming film will star both…

Shaun of the Dead’s Nick Frost joins the cast of Universal Pictures’ live-action How to Train Your Dragon remake.

Netflix has dropped a brand new trailer for its upcoming animated fantasy movie, Orion and the Dark. The trailer features…

Disney has revealed the Wish digital, 4K, Blu-ray, and DVD release dates for the newest Walt Disney Animation Studios film.…

Stranger Things star Eduardo Franco, who played Argyle in Season 4, has said that he won’t be returning for the…

To celebrate the 85th anniversary of The Wizard of Oz, Warner Bros. has partnered up with Fathom Events for upcoming…

The curse isn’t over yet. Paramount Pictures’ untitled sequel to Smile has rounded out its cast, with Kyle Gallner (The…

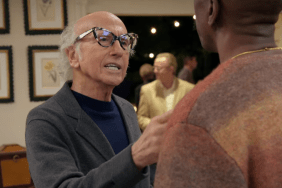

Max has released the first Curb Your Enthusiasm Season 12 trailer, providing the first look at the final season of…

According to Deadline, Max has opted to not renew its Julia Child-centered comedy drama series for a third season. The…

Reviews and Previews

We’ve all had horrible neighbors at some point. Most of us don’t accidentally kill them, though, no matter how loud…

Twin Peaks set-up, Crucible execution.

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water, director Bryce McGuire gives the world Night…

Warren Fast’s Roadkill sees a young woman and a drifter end up in a murderous situation that twists and turns…

Interviews

ComingSoon Senior Editor Spencer Legacy spoke with Role Play stars Kaley Cuoco and David Oyelowo about the Prime Video action…

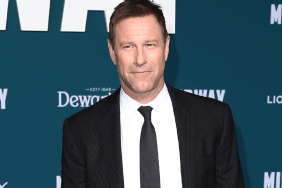

ComingSoon Editor-in-Chief Tyler Treese spoke with The Bricklayer star Aaron Eckhart about the intense action movie. The actor discussed how…

ComingSoon had the opportunity to interview Brandon McLaughlin, the special effects coordinator for Killers of the Flower Moon. During the…

ComingSoon Editor-in-Chief Tyler Treese spoke with Good Grief writer, director, and star Dan Levy and stars Ruth Negga and Himesh…

Anime

Revenge Manhwa is pretty famous, whether it be petty or violent. However, what can be better than finding a story…

The upcoming Mobile Suit Gundam SEED Freedom movie is a part of the Mobile Suit Gundam SEED project. The project…

Excitement is building among anime enthusiasts as Netflix announces the release date for Monsters. This is a highly anticipated One…

In Gege Akutami’s Jujutsu Kaisen, all the sorcerers use different cursed techniques. The cursed technique wielders can use these techniques…

Horror

The Child’s Play remake by Lars Klevberg (Polaroid) is receiving a 4K collector’s edition soon from Scream Factory and Orion…

Altitude Film Entertainment has released a No Way Up trailer to showcase its intense sharks on a plane disaster movie.…

Gremlins star Zach Galligan stars in the anthology horror movie Midnight Peepshow, which has received a new trailer. Midnight Peepshow…

Twenty-two years after 28 Days Later, director Danny Boyle and writer Alex Garland are reteaming with plans for a second…

Indian Movies & TV

Tu Jhoothi Main Makkar (TJMM), a Hindi-language romantic comedy, released on March 8, 2023. It is directed by Luv Ranjan,…

Katrina Kaif and Vijay Sethupathi are currently shining on the big screen with their latest thriller, Merry Christmas. The two…

Malayalam star Mohanlal is known for signing the most unique films. He is one of the best actors in Malayalam…

Teja Sajja‘s much-awaited superhero film HanuMan finally hit theaters on Friday, January 12, 2024. Following its theatrical release, the movie received…

Korean Drama

Like Flowers in Sand episode 8, starring Jang Dong-Yoon as Kim Baek-Du and Lee Joo-Myoung as Oh Yu-Gyeong/Du-Sik, aired on…

Episode 5 of the revenge K-drama Marry My Husband, starring Park Min-Young, will arrive on Monday, January 15, 2024, on tvN. The episode…

Episode 4 of Transit Love (EXchange) season 3 will air in January 2024. Directed by Kim In-Ha, ever since the dating show…

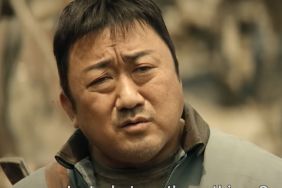

Netflix’s upcoming South Korean action thriller Badland Hunters is set to premiere on Friday, January 26, 2024. The film, featuring Ma Dong-Seok (Don Lee) in…

Marvel and DC

Ahead of its digital and home video releases, a brand new The Marvels deleted scene from Marvel Studios’ latest superhero…

After watching Echo, many fans wish to find out about the Queenpin. Who is she and will Echo get this…

With the arrival of Echo in Phase 5, many fans wonder about its place in the ever-growing MCU timeline. Where…

Filming on Marvel’s Fantastic Four movie has allegedly been pushed back from April of this year to Q3 2024, seemingly…

True Crime

Disclaimer: This article contains mentions of murder and blood. Readers’ discretion is advised. Jennifer Dulos‘ case recently resurfaced as a…

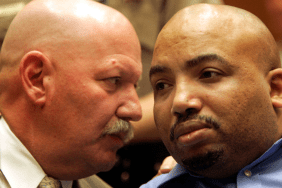

Dateline NBC plans to re-examine the gruesome murder-for-hire plot that killed Ted Shaughnessy in 2018. The upcoming episode, titled ‘Ghosts Can’t Talk,’ will…

Disclaimer: The article contains mentions of abuse and murder. Readers’ discretion is advised. Chester Turner is an American serial killer…

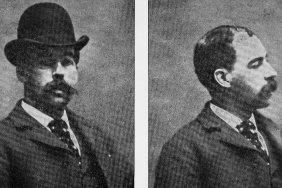

Disclaimer: The article mentions murder and violence. Readers’ discretion is advised. H. H. Holmes is an American serial killer who…

Guides

Designing Women Season 5 is a beloved television sitcom created by Linda Bloodworth-Thomason that follows the lives and careers of…

Wondering how to watch and stream Fluffy Paradise Season 1 Episode 3 online? Look no further, you have come to…

The Fluffy Paradise Season 1 Episode 3 release date and time have been revealed. The episode will air on Crunchyroll.…

Killers of the Flower Moon is a crime drama flick helmed by Martin Scorsese, popularly known for his box office…